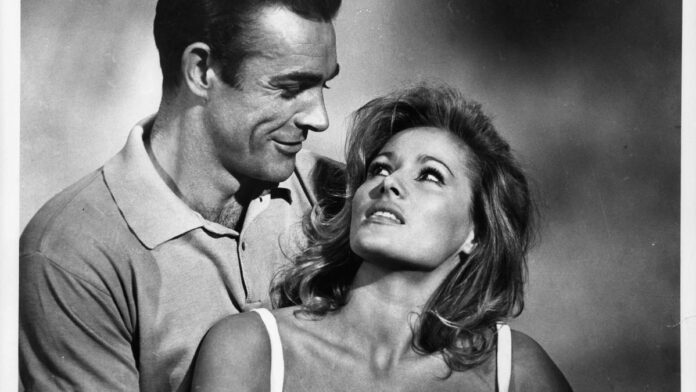

Sean Connery and Ursula Andress in the film ‘James Bond: Dr. No’, 1962.

| Photo Credit: Getty Images

One of my favourite James Bond sequences in recent times is the interrogation scene from Sam Mendes’ Skyfall (2012). The film’s antagonist Raoul Silva (Javier Bardem) is being questioned by M (Judi Dench), the still-formidable head of MI6. Silva holds a grudge against M because when he was an active MI6 agent in Hong Kong under her command, she betrayed him and gave him up to the Chinese government who then tortured him horribly. Even when I had watched this scene in the theatre for the first time, it struck me that the dynamic between M and Silva was intended as a nod to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. The name of the film itself is the name of the Scottish castle Bond grew up in — a classically Gothic setting, it has to be said.

Ian Fleming, British author and creator of James Bond, at his desk in his study, in 1958.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

A collection of Ian Fleming’s James Bond 007 books at an exhibition at the Imperial War Museum, London.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

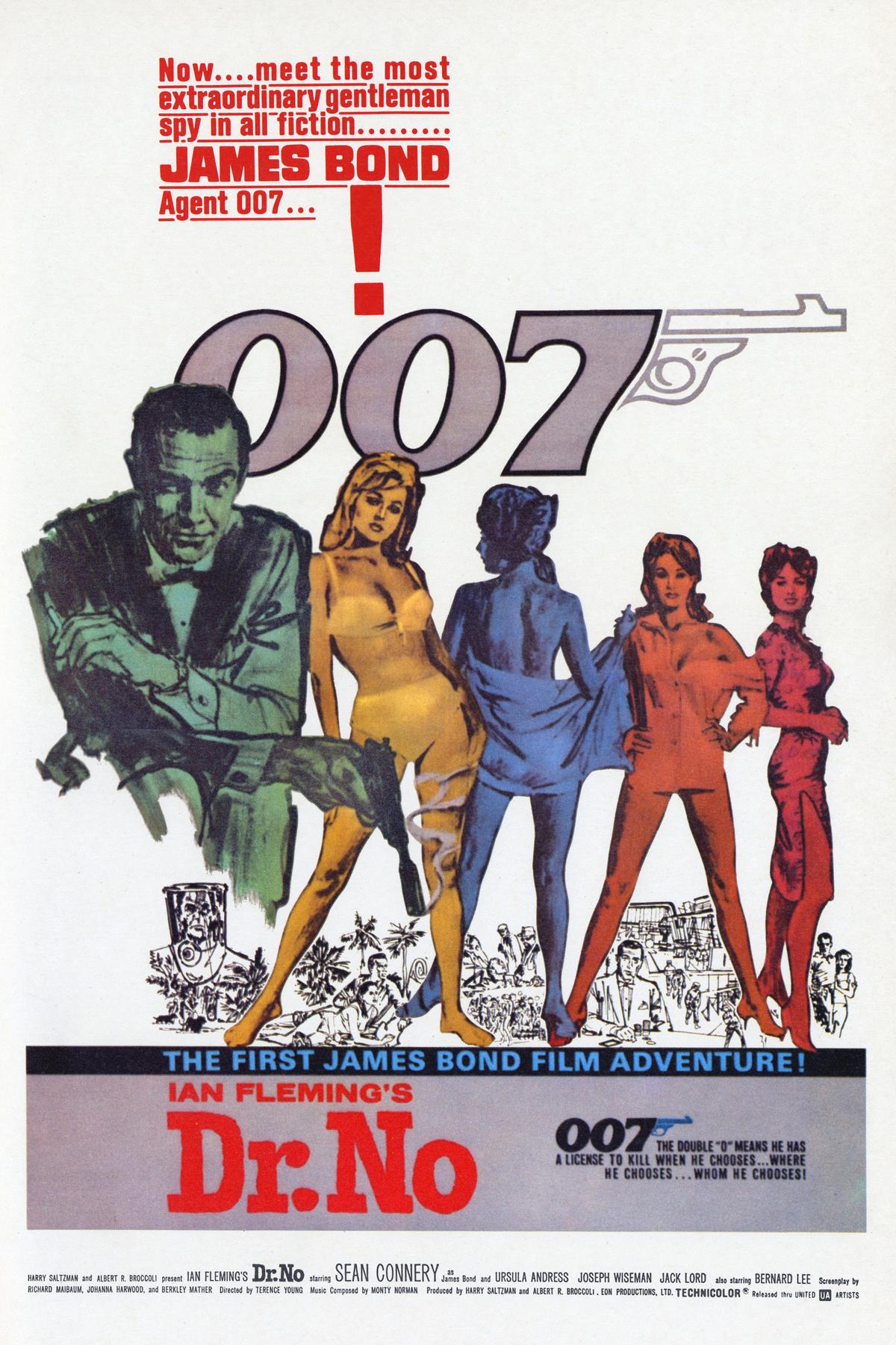

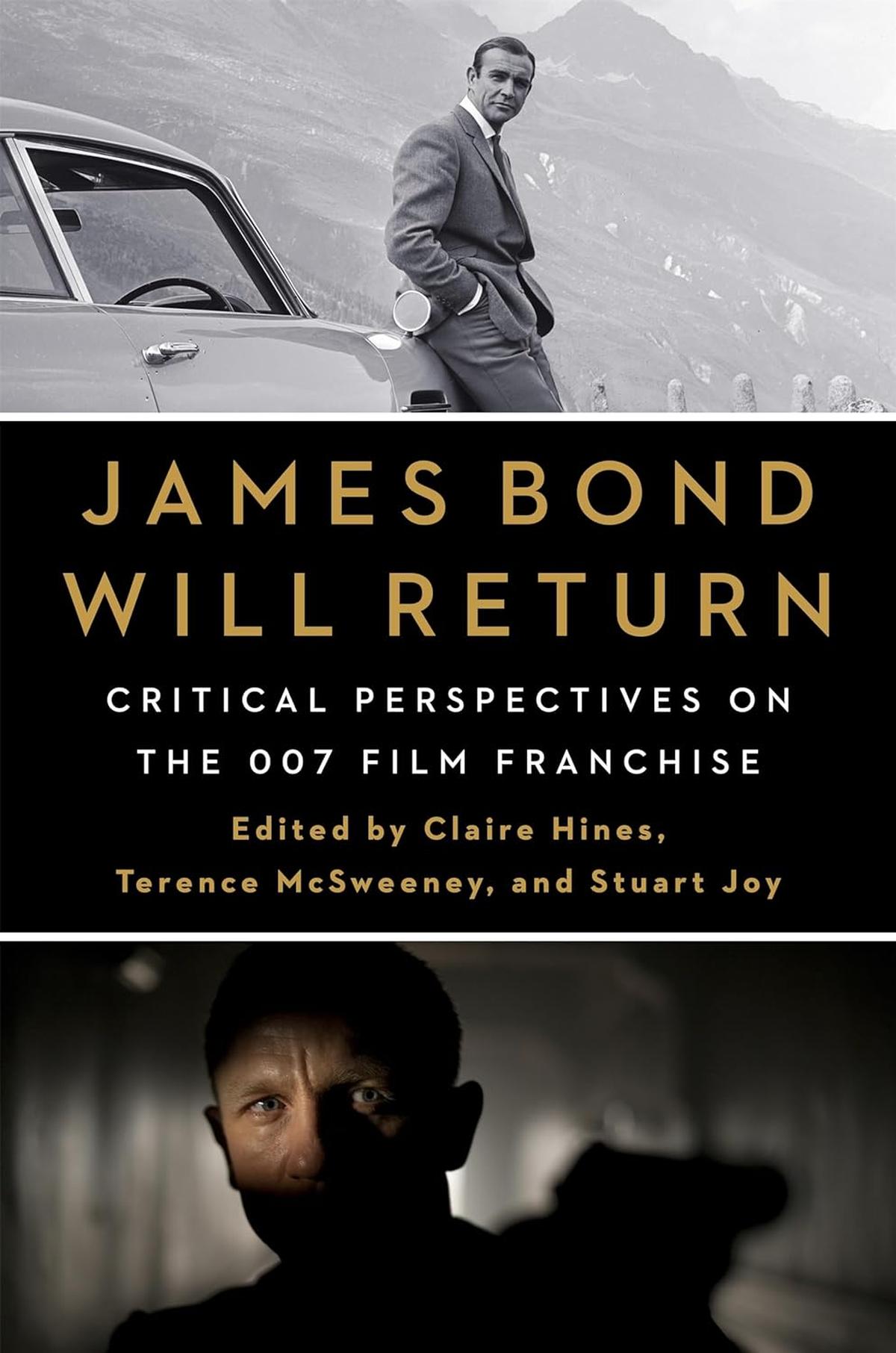

This parallel between the film and Shelley’s novel is the cornerstone of Monica Germanà’s excellent essay ‘Sometimes the Old Ways Are the Best: Technology and the Body in a Gothic Reading of Sam Mendes’ Skyfall.’ The essay is a part of the recently published collection James Bond Will Return: Critical Perspectives on the 007 Franchise, edited by Claire Hines, Terence McSweeney and Stuart Joy. This wide-ranging collection goes through the 007 canon in chronological order, starting with an essay about the first Bond film (Dr No, 1962) and ending with an essay about the most recent one (No Time to Die, 2021).

A still from ‘No Time to Die’.

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Clash between old and new

As Germanà notes in her essay, the Frankenstein parallels also work very well with the film’s other overarching concern: the clash between “the old ways” of spycraft and warfare vs the new ways (hacking, electronic surveillance). In the face of a technologically astute supervillain like Silva, Bond ‘recedes’ into a kind of defensive Luddism, abandoning the gadgetry that contemporary Bond fans would be used to. He even goes back to the Sean Connery-era classic Aston Martin, even as M turns up her nose at this ostentatious relic of a car. In the climax of the movie, as Silva uses his tech-wizardry in his relentless pursuit of M, Bond eventually kills his adversary with an old-school hunting knife. The essays are enjoyable not just because of the depth of the analysis but also for the way they bring together visual, textual and design elements in their readings of the 007 films.

A poster of the film ‘Dr No’.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

Here, for example, is Germanà noting the visual resemblance between Silva and the real-life hacker Julian Assange, especially their blonde hair.

“Seen as a reaction to MI6’s merciless exploitation of its own agents, Silva’s cyber-attack points to the subversive politics of data hacking, a fact underscored by Silva’s alleged resemblance with WikiLeaks hacker Julian Assange. As ‘illegal’ code-cracking juxtaposes ‘formal institutions… which were previously able to dominate access to information and… dissidents, who, with growing confidence, are able to circumvent traditional networks through technology,’ the film traces a fine line, arguably, between rebellious hackers and cyberterrorists.”

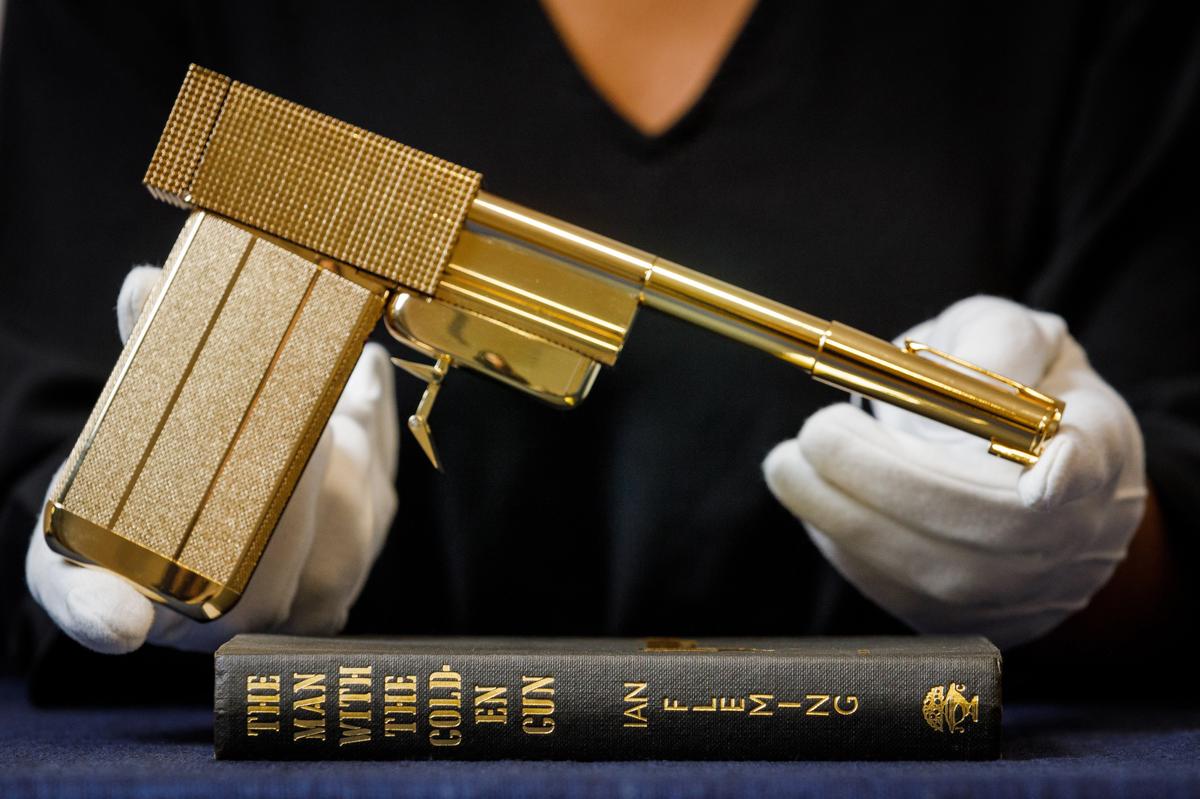

A limited edition replica of the gun from the film The Man with the Golden Gun (estimate £6,000 – £9,000) alongside a first-edition book (estimate £4,000-£6,000) by the same name, on display at Sotheby’s.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

The editors have done a fine job in balancing the theory-heavy essays with other entries that are more focused on the praxis and politics around filmmaking. The Bond franchise itself, based on Ian Fleming’s novels, is a kind of convoluted metonym for Britishness, but the business of filmmaking is rooted in Hollywood ethos — the resultant narrative tension is apparent in the films (especially in the 21st century when the scale of Hollywood means that producers are looking for ‘bankable’ stories). The British vs American clash of values is partly responsible for some of the franchise’s notable misfires, like Spectre (2015). James Smith’s essay ‘It’s Always Been Me: Spectrality, Hauntings and Retcon in Spectre’ expertly dissects some of the film’s narrative confusions and failures. ‘Retcon’ or ‘retroactive continuity’ is a term originating in the comicbook industry, used to describe a situation where writers on a long-running media franchise change previously-established truths or realities, thus ‘overwriting’ the works of their predecessors.

Why ‘Spectre’ misfired

Spectre’s retcon is clumsily done not just in terms of scale — every previous villain in the Bond era being revealed to be pawns of the same organisation — but also in terms of tenor. The overall direction of the Daniel Craig-era movies involved a resetting of 007’s more problematic gender-related and geopolitical themes. Spectre seems to want to undo that whole bloc of stories, but its execution is frequently subpar.

An Aston Martin DB10, produced exclusively for Spectre, and a James Bond costume on display at the London Film Museum.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

As Smith writes, “The retcon is illustrated for the audience in other ham-fisted ways: Blofeld takes the trouble to decorate the ruins of MI6’s headquarters with A4 printout photos of Bond’s deceased friends and foes, unfortunately giving the sense more of a site-specific art project than some terrible act of revenge. His attempts to zombify Bond meanwhile prove strangely ineffective, Bond jumping to his feet little the worse for wear even after having a hole drilled through his brain.”

Actor Roger Moore on the set of ‘Octopussy’.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

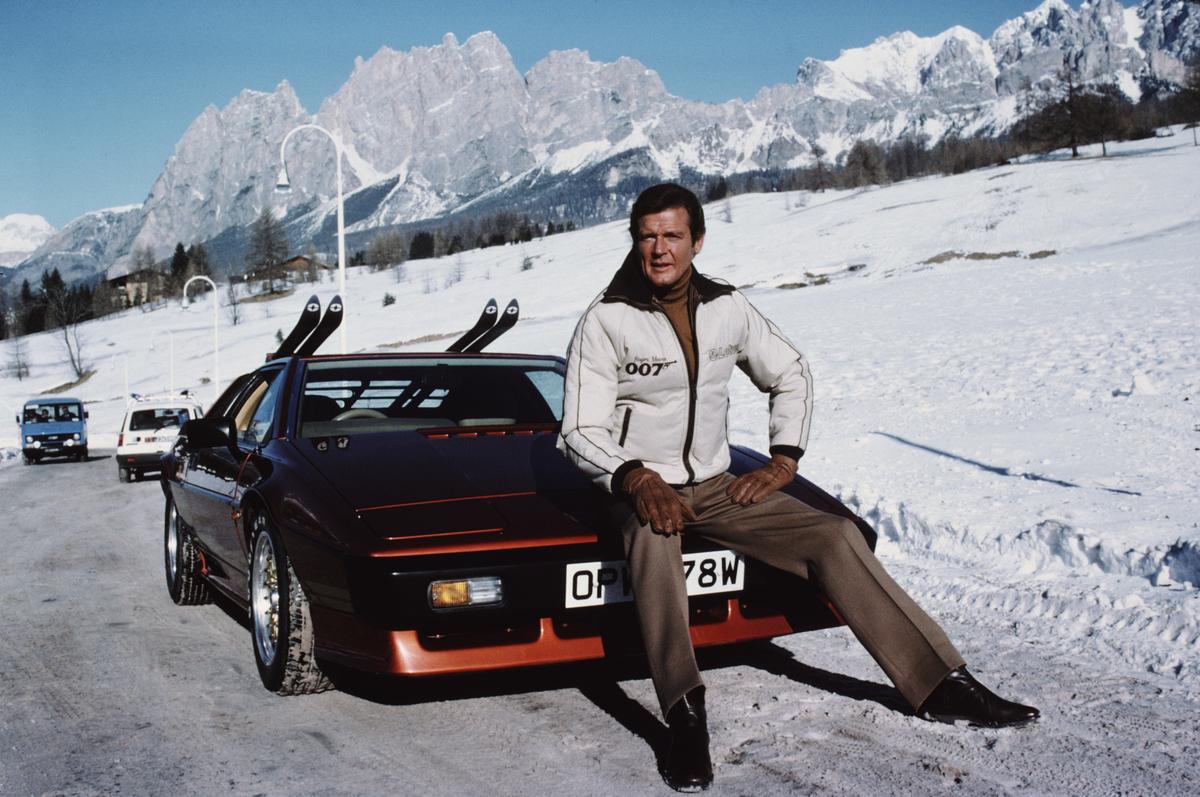

Claire Hines, one of the editors of the book, is similarly astute in her own essay, a study of costumes and gender performance in Octopussy (1983), one of the most visually interesting films of the Roger Moore era. I also enjoyed Stuart Joy’s study of vendetta themes in For Your Eyes Only (1981). For fans of the Bond franchise, James Bond Will Return is a must-read. For everybody else, it presents an intriguing starting point into Bond-lore.

Actor Roger Moore poses as 007, with a Lotus Esprit Turbo, on the set of For Your Eyes Only, 1981.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

James Bond Will Return: Critical Perspectives on the 007 Franchise; Edited by Claire Hines, Terence McSweeney, Stuart Joy, Columbia University Press, ₹2,733 (Kindle).

The writer and journalist is working on his first book of non-fiction.

#Parallels #Frankenstein #Hindu