The Madras Observatory, established in 1792 by the East India Company, is testament to the intertwined history of science, colonialism, and innovation in India. Its legacy is etched on its granite pillars and the astronomical discoveries it fostered continue to resonate today.

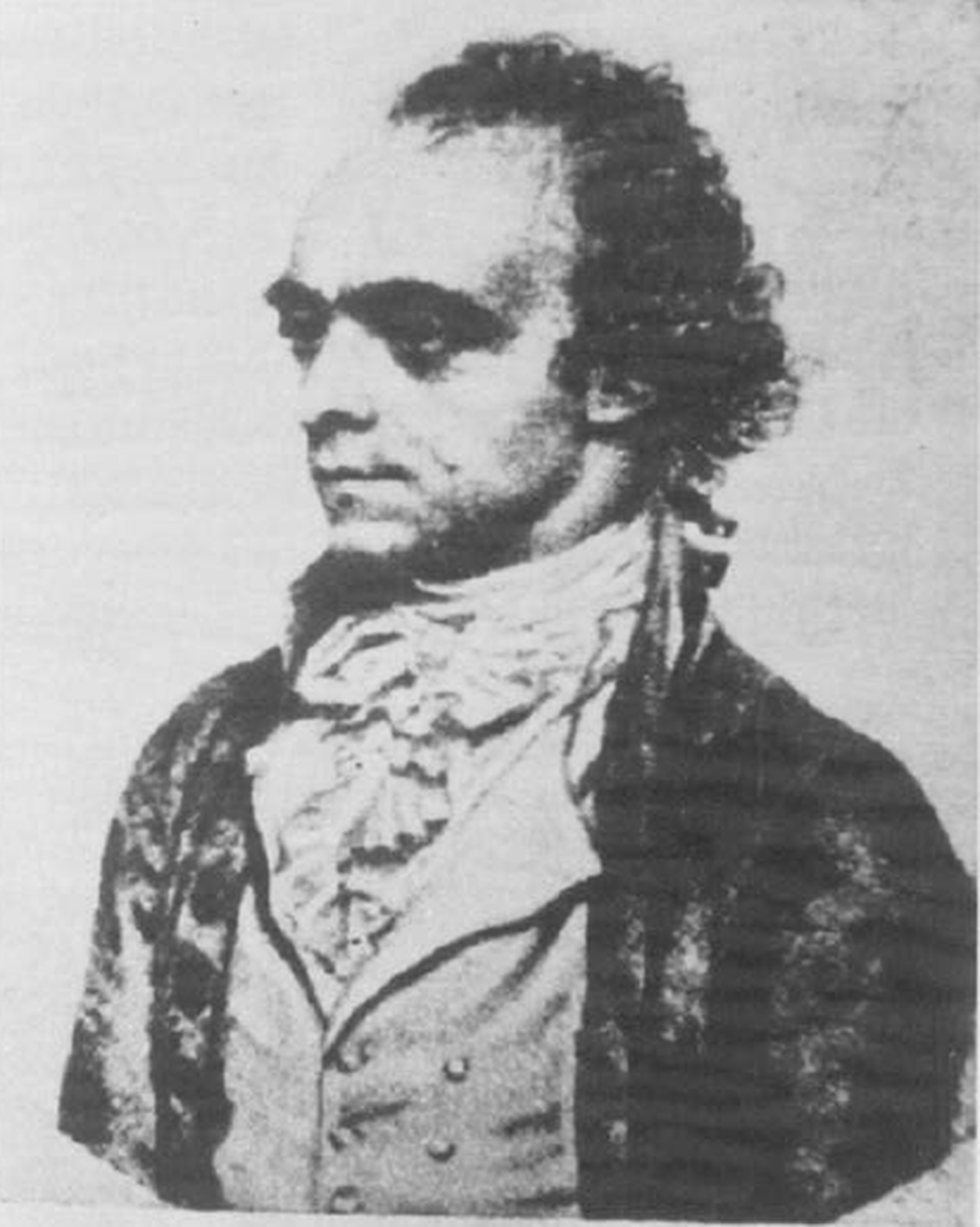

The story begins in 1785 with the arrival of Michael Topping, an astronomer and surveyor employed by the East India Company. Tasked with enhancing navigation in the region, Topping charted the Coromandel coast and currents of the Bay of Bengal between Madras and Calcutta.

According to the UNESCO Portal to the Heritage of Astronomy, at the time, William Petrie, member of the Madras Governor’s Council, had already established a private observatory at his Egmore residence. On December 5, the longitude and latitude of Masulipatnam were recorded, likely at Petrie’s observatory. This observatory, equipped with instruments like a 20-inch transit and a 12-inch azimuth transit circle instrument,which were owned by Petrie, made up the nucleus of the Madras Observatory. When Petrie returned to England in 1789, he handed over the equipment to the Madras Government.

“The exact location of Petrie’s home observatory in Egmore is unknown to us, but it could just be a confusion, as Nungambakkam becomes Egmore. For all we know, it could have been the same location,” says historian V Sriram.

Michael Topping

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

Recognising the scientific and strategic value of such a facility, Topping urged the Council to establish a dedicated observatory. His appeal, echoing a previous plan by engineer Patrick Ross, finally swayed the Court of Directors in London, who sanctioned the observatory’s construction in 1790. Two years later, in 1792, the Madras Observatory was inaugurated, housing Petrie’s instruments and a conical pillar designed to support a 12-inch azimuth (an instrument that helps provide the horizontal coordinates of an object in the sky).

Madras Observatory in Chennai, designed by Michael Topping (1792), 1880 (Government of India, 1926)

John Goldingham, who had served as Petrie’s assistant, was appointed as the observatory’s first official astronomer. Goldingham’s tenure, lasting until 1830, was marked by significant contributions. He initiated meteorological observations in September 1793, meticulously recording data that would form the foundation of India’s earliest meteorological records. These records, along with a meteorological register established in 1796, provide invaluable insights into the region’s climatic history.

In 1802, the Madras Time Zone was established by Goldingham, which is also known as the Railway Time. When the British colonised India and introduced the Railways, it came to their attention that time was not standardised throughout the country. Bombay and Calcutta had their own time zones which made operations difficult. Just as they had standardised time in England according to the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, they did with the Madras Observatory in India. The Madras Time, till date, is followed as the official time of the Indian Railways.

Beyond his meteorological work, Goldingham also ventured into the realm of acoustics. Leveraging the city’s landmarks — the Madras Observatory, Fort St. George, and St. Thomas Mount — he conducted experiments to determine the velocity of sound. By measuring distances using Lambton’s Great Trigonometric Survey and analysing 808 cannon reports over 18 months, Goldingham established the velocity of sound, accounting for factors like temperature, humidity, and wind’s direction.

Following Goldingham, Thomas Glanville Taylor assumed the role of Government Astronomer in 1830. Taylor, during his tenure until 1848, focussed on astrometry, mapping the positions of stars in the Southern Hemisphere. His efforts culminated in the publication of a comprehensive catalogue of 11,000 stars in 1844, significantly expanding the known celestial map.

The year 1861 marked a turning point for the Madras Observatory with the arrival of Norman Robert Pogson as government astronomer. Pogson introduced the observation of variable stars and minor planets to the observatory’s research agenda.

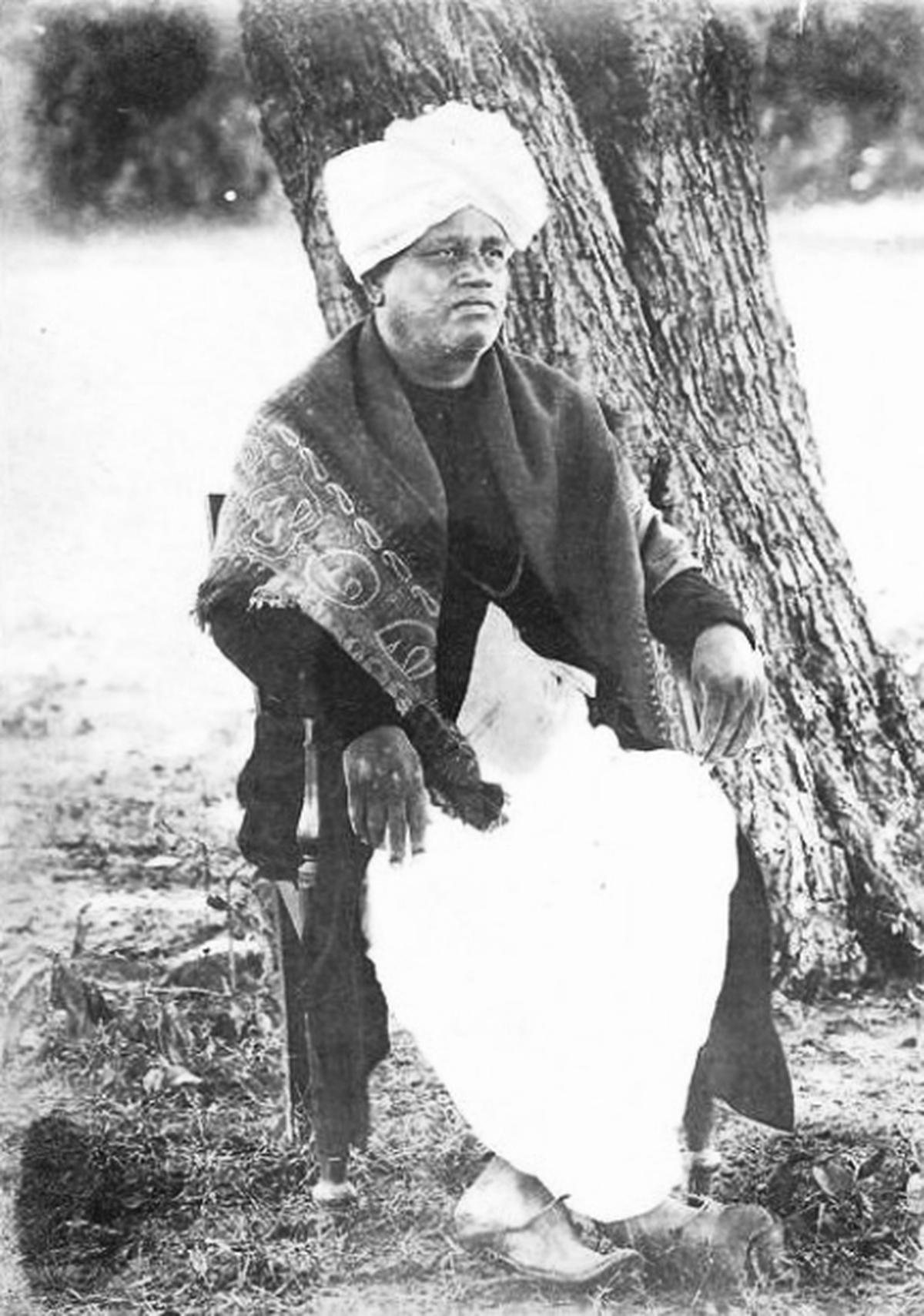

Chinthamani Ragoonatha Charry

| Photo Credit:

Wikipedia

Among the observatory’s staff during this period was Chinthamani Ragoonatha Charry, an observer who had joined in 1847 and risen to the position of first assistant. Recognising Charry’s talent, Pogson mentored him, and in January 1867, Charry made a significant breakthrough, discovering the variability of the star R Reticuli. His observations over a period of nine months revealed that the star reached peak brightness in mid-February. This discovery solidified Charry’s place in astronomical history, making him the first India-born astronomer to publish in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society and later, the first Indian to become a fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1872.

However, the Madras Observatory’s time in Madras was drawing to a close. In 1899, as part of a reorganisation of Indian observatories, the astronomical equipment and a portion of the staff were transferred to Kodaikanal, a location deemed more suitable for astronomical observations due to its favourable climate. The Madras Observatory, while continuing to conduct transit observations for timekeeping, shifted its focus to meteorology, eventually becoming the Indian Meteorological Department’s Madras office. “It was only in 1931 that the Madras Observatory was completely shut down,” says V Sriram.

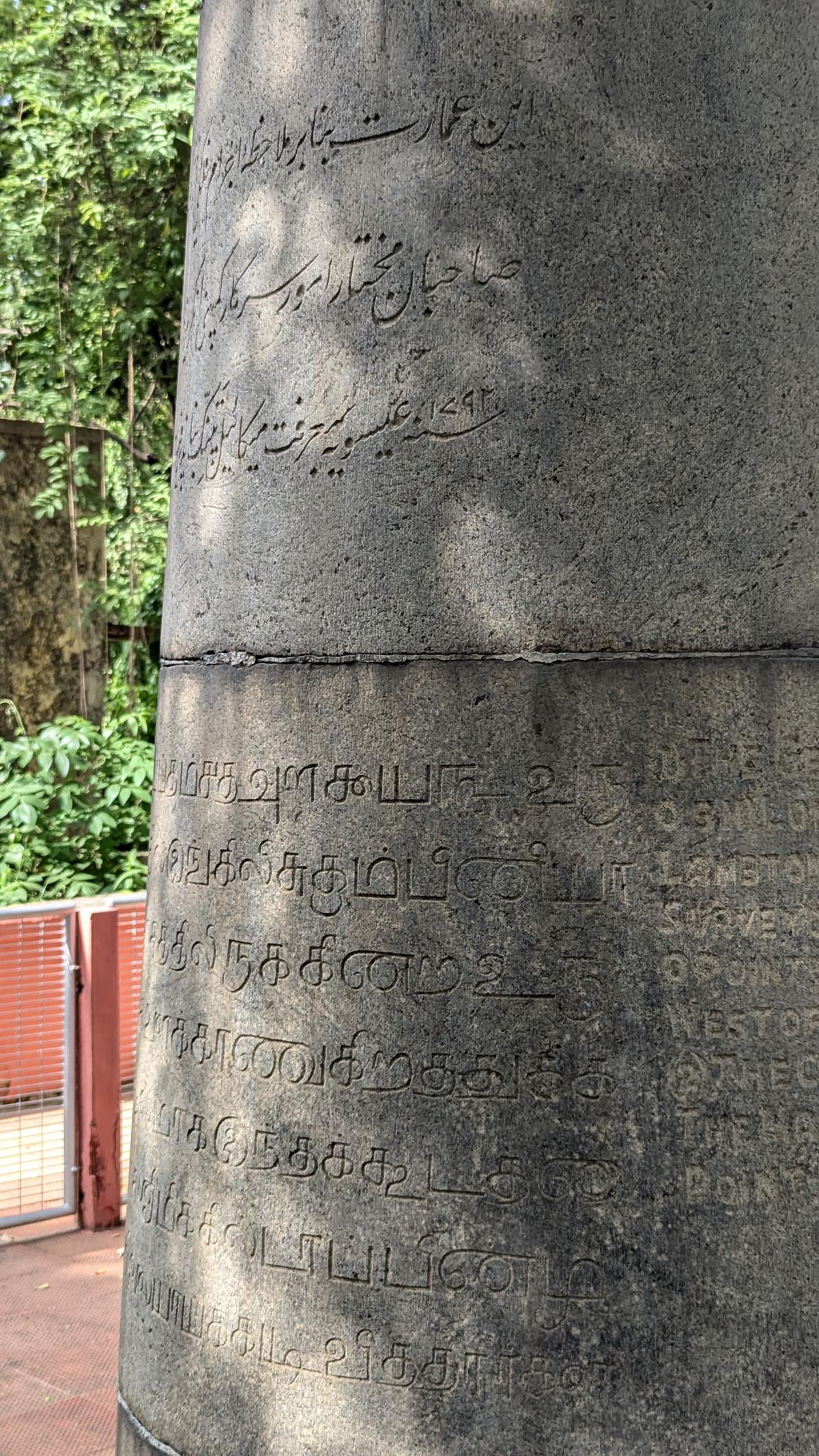

The Madras Observatory, considered the first modern public observatory in India, and possibly of the East, endured a legacy both in its physical remnants — the granite pillar, bearing Topping’s name and astronomical inscriptions, still stands as a monument in the IMD campus, Chennai — and in the discoveries it nurtured. The observatory’s contributions to our understanding of the cosmos, weather patterns, and sound reflect its enduring scientific significance.

#Madras #Observatory #paved #significant #astronomical #discoveries