It is my experience that interviewees are rarely interested in you. Occasionally, at the end of the meeting, they may lean back and ask a couple of cursory questions about your work. But, on a Wednesday evening at the Kerala House in Delhi, K.K. Shailaja had barely walked into the room before I was peppered with half a dozen questions. Where was I from, what did my parents do, do I have children, what is my daughter’s name. Her interest in my life was at once uplifting and endearing, and it was easy to see then how this MLA and Kerala’s former “rockstar” health minister emerged as a calm and efficient presence at a time when the world was a bewildering place stalked by an invisible killer virus. She envelops both, a comforting maternalism as well as a teacherly authority.

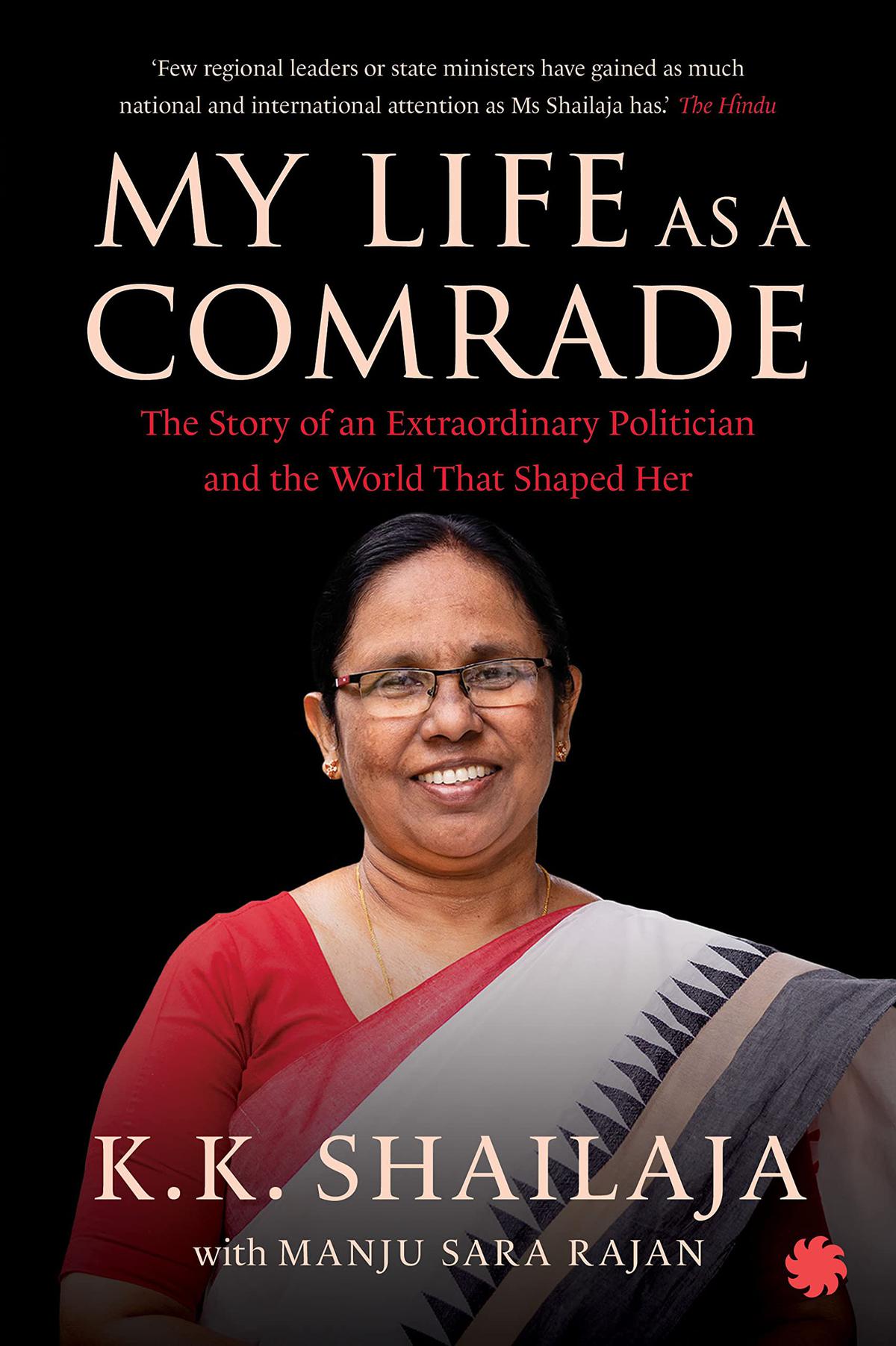

In her new book, My Life as a Comrade, co-written with Manju Sara Rajan, former CEO of the Kochi Biennale Foundation and journalist, Shailaja writes about the course of her life that started in a small settlement in Malabar and eventually led her to a Cabinet position in the State government. She was born in a family that was fiercely political for at least two generations prior. In the 1930s, her grand uncles were participants in the early stages of communism in Malabar, they fought for farmers’ rights, courted arrest several times and the most fierce of them, M.K. Ravunni died from injuries sustained while incarcerated. Their sister, Shailaja’s grandmother, also stepped into the agitation, helping hide party workers, and looking after the sick and the poor.

The class divide and the political circumstances at the time decided the course of the family, and in that sense, Shailaja’s association with the Communist Party was an eventuality that was determined even before she was born. “If we hadn’t been part of Kannur, perhaps we would have been a very different people making very different choices,” she writes. But as things stood, she came from a family of political workers, which she goes to great lengths to explain, is different from politicians. She started as one and ended as the other.

K.K. Shailaja visiting a disaster-struck area in the State

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Calm in a crisis

Shailaja explains her career as a series of small steps, starting as a party worker, a teacher by day, a social activist in the evening, until the Party bestowed her a ticket to fight the 1996 Assembly election that she won. When denied a ticket for a second term, she quietly went back to being a teacher and a political worker, until she was given a chance again. The third time around, she also got a Cabinet position and became the minister of Health, Family Welfare and Social Justice in 2016, in Pinarayi Vijayan’s first term as chief minister of Kerala.

These were difficult years for the State, ravaged as it was by cyclones and disease. The first big health scare came in 2018 with the Nipah virus and Shailaja plunged deep into it, building a multi-skilled team around her, looking at every aspect of fighting the outbreak, from containment to communication. Therefore, a couple of years later, when COVID-19 hit (the first cases in the country were in Kerala), the health ministry had a plan ready. Through that crisis, Shailaja emerged as a calm and competent health minister, one who was following the science and doing most things right. U.K.’s Guardian newspaper called her a “rockstar”, a compliment that led to comical confusion in the opposition. Yet, in 2021, even though she posted a landslide victory, she did not find a place in the Cabinet.

K.K. Shailaja promotes the use of sanitisers as part of the ‘Break the Chain’ campaign launched by the State government

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Shailaja’s political story is one of unquestioningly toeing the party line, and, as she tells me, being committed to political work, as opposed to political power. But this is a simplistic and reductive narrative, I point out, a journey like hers has to be fuelled by ambition. “As human beings, we are always dazzled by power and glory. But I am not possessive about positions such as being an MLA or MP. If any such feelings enter my mind, I remind myself of the many women working selflessly. If you are disappointed by not getting positions of power, you should quit politics,” she says.

Kerala Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan and K.K. Shailaja

| Photo Credit:

Mustafah K.K.

Of feminism and responsibility

I bring her to the other thread that runs through the book, her feminism, which she does not refer to by its name. Both Shailaja’s grandmother and mother were single mothers. Her grandmother was an opinionated, strong woman, fighting against classism and casteism. A few years after her marriage, her mother discovered that her husband had another partner and a child. Despite the fact that at the time people did not go to court over family matters, she was determined to get a divorce.

Shailaja’s marriage too had an unconventional power balance. Her husband, K. Bhaskaran, encouraged her to throw herself into party work, while he held down the fort at home. For someone who has upended ordinary gender conventions, why doesn’t she call herself a feminist? “I am a feminist, but I am not a radical feminist,” she says.

“True feminism is equality, a comradely relationship and the ability to live with dignity. Radical feminism is the freedom to be anything or do anything. Freedom should be compatible with society.”

What is radical feminism according to you, I ask, and I am worried that she will cop out and give me a version of feminism that is not so much about equality but about making small adjustments to patriarchy. But she dials back to the history of feminism and the class struggle from the 1920s. “If you look at the history of feminism, especially in the early 20th century, while western feminists were burning their bras, in our parts we were struggling for the right of lower caste women to cover their bodies. There cannot be a uniform and singular demand for all feminists. True feminism is equality, a comradely relationship and the ability to live with dignity. Radical feminism is the freedom to be anything or do anything. Freedom should be compatible with society.”

K.K. Shailaja

| Photo Credit:

V.V. Krishnan

This is not a convincing argument for me, but it is entirely a reflection of how she has lived her life. At various points in the book, she writes about her anguish about not spending enough time with her children. She blames herself for not being around when her son had to be taken to the hospital for shoving a seed deep inside his nose. This maternal guilt is a familiar trope that no one, not even “radical feminists” find easy to overcome. “This has been a constant struggle in my life,” she says. “At home, I always felt that I wasn’t doing enough. I am not alone. So many women are trying to solve this problem.” This is real life and to her there is no conflict between her philosophy and her feelings.

Shailaja attributes her success to her sense of absolute responsibility and her skill of building a team of committed people. But, to my mind, it is her ability to keep it real, a genuine interest in others, and a life of empathy that makes her stand out. This may sound easy, but these are very rare traits. After all, we have 28 States in the country, how many other health ministers can you name?

The book, published by Juggernaut and priced ₹799, is out today.

The writer is the author of ‘Independence Day: A People’s History’.

#Teacher #rockstar #Shailaja #book #Life #Comrade