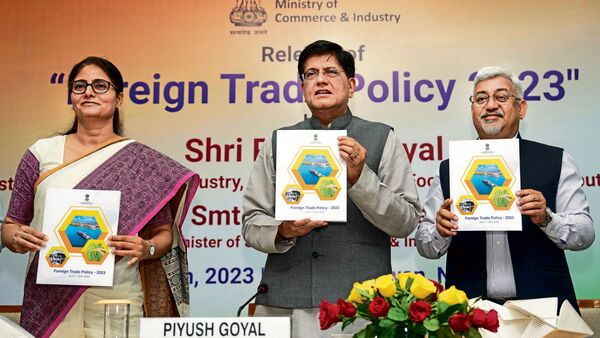

India’s new Foreign Trade Policy (FTP), unveiled on Friday by commerce minister Piyush Goyal, took some time coming. The last one was meant for a five-year span that ended just as covid began in March 2020. This one has no expiry date, but it sets an export target of $2 trillion by 2030, up from goods and services worth roughly $750 billion that we expect to log in 2022-23. Apart from easing trade in general, its chief aim is to align Indian exports with a big global e-commerce opportunity within World Trade Organization (WTO) rules that disallow openly visible export incentives. To that end, a slew of facilitation measures will be rolled out, while a recent tax remission system that replaced WTO-axed props will be widened to relieve more shipments of domestic levies. This is well in sync with a renewed push for a competitive edge overseas amid high levels of flux. The world’s economic expansion is set to lose pace and free trade has been losing traction as a doctrine. Plus, the rupee tends to pivot on capital flows, which thwarts its role as an adjuster of trade flows, even as demand for Indian services keeps our currency dearer than what merchandise exporters may need against foreign rivals. As a major economy, we still punch far below our weight in world trade, success with which is vital; isolation has long proven a failure, with Asia’s rise having left it in the dust heap of bad ideas. To engage the globe, however, cogency of policy is key. Two aspects need a closer look.

First, take the FTP’s effort to ease exports. As proposed, online approvals will be stepped up for various schemes, with some processes automated, among other tech-enabled snips of red tape. The country’s exporter ‘status’ regime has also been recast to enlist more beneficiaries. If all goes by plan, targeted tweaks will be made in support of major sectors like dairy, textiles and apparel, export obligations will be eased for items that go into climate action, and e-com export hubs will be incubated. And while a limit on the value of courier despatches was not removed (as it should’ve been), it was doubled to ₹10 lakh. As with moves to enable trade deals in rupees, all these count as micro-reforms. What looks askew from the ‘Make in India’ thrust of Atmanirbhar Bharat, though, are the FTP’s enablers of trade done by merchants among other countries with no Indian ports involved. While this aims to help local players exploit wider opportunities, it could also support a trend of investors putting money into plants abroad to serve global markets. But then, being pro-trade by trying to push exports and deter imports can pose other riddles as well.

Our second major policy gap is visible in the country’s maze of import tariffs. Let alone fields fenced off for champions of self-reliance, our duties remain relatively steep even on average. This may reflect raw nerves exposed locally, the sort that partly pulled India out of a project to dissolve Asian barriers, but in shielding our home base from global rivalry, we also elevate the overall cost base—as market forces wind around to ensure. Moreover, with some edges sharpened and others blunted, uneven tariff lines create both winners and losers; getting this mix right may require skills whose scarcity looks likely to worsen in such dynamic times. Although an expiry-free FTP that’s open to change would grant the Centre flexibility, it could also spell ‘policy instability’ should it fail to settle, making it harder for India to snap into China-plus value chains. Given such risks, we must minimize dissonance to the extent we can.

Download The Mint News App to get Daily Market Updates.

More

Less

#Harmonize #trade #policy #Indias #broad #goals